Differentiation & Distinctiveness - A Mayo Sandwich Perspective

"We walk a dangerous path when we stop knowing who to believe."

A LinkedIn post by Gavin Merriman (Head of Consumer -APAC Moët Hennessy), a few weeks ago, echoed much of the frustration I am observing as the food-fight over differentiation and distinctiveness reaches spicier levels.

At the end of each day, under increasingly tough market conditions, all that great marketers want to do is, is to make the best possible long versus short-term brand-building and investment trade-offs, given the limit resources at hand.

Here are my thoughts and contribution to the discussion.

A great mayo, a great sandwich maketh

All I want is a great sandwich. One caressed with great mayo. But, can you please use Hellmann’s.

Slathering Hellmann’s on hot-from-the-oven, crusted bread that is layered with all sorts of wholesome sandwich layers is my go-to-treat for a light weekend lunch.

Hellmann’s is always in my refrigerator.

Do I like the “REAL” taste? Yes. I like it better than many others! Most sandwiches are elevated with great mayo!

Ingredient integrity? A cleaner list would have been preferable. (Sir Kensington's has one, but I cannot always find it easily.)

Good price point? A great Costco deal on a $/oz basis. Also, it seems to always be on special somewhere.

Availability? Hellmann's I can find almost everywhere! The Best Foods twin, though, confuses me when I visit other states. It's even in Aldi, but I guess mostly to act as an anchor price so that they can sell their clone.

Sustainability? Unilever's commitment certainly factors into my world view and makes me like Hellmann's a bit more, but I would have purchased it anyway.

Convenience? Have you even tried to make your own mayo? It can be a mission. Reaching for Hellmann's is so much easier and less messier. (Hint: If you are going to make your own get a Bamix mixer!)

Logo familiarity? The consistent blue ribbon logo shape and yellow splash now symbolizes safety and trust for me. Funny how that works.

All the above? Absolutely!

I guess you can say that my ongoing choice for Hellmann’s is highly influenced by mental triggers that, for me, have made the brand both seemingly differentiated and distinctive in some way.

For somebody else, the attribute mix listed above might look different or even be irrelevant. Any mayo might do. That’s ok too. Lots of people buy mayo.

A core marketing goal is to find creative ways that can build a brand’s appeal and its reach to and for as many consumers as possible. This means for different consumers, different consumption occasions...as margin-effectively and margin-sustainably as possible. Heavy, medium, and light buyers. Buyers that care for some mix of attributes and buyers that don’t.

Over decades, a dynasty of Unilever marketers and product innovators have toiled to craft a product and brand with attributes and with an identity that obviously means something to me and many others. They have built equity.

It’s interesting how some of these attributes come to mind every time I enter that category. Basically, every time when I need to make a wholesome sandwich for a weekend light lunch...I’m nudged to pick up Hellmann’s.

Graphic #1:The Mayo Consumer Need State and Category Entry Point

Hellmann's is Easy to Buy...

Byron Sharp (Professor of Marketing Science, Director & Author) and Jenni Romaniuk (Research Professor & Author), both of Ehrenberg-Bass Institute of Marketing Science, have challenged many marketing myths with their groundbreaking research on brand growth. (See references [1] and [2]. Excellent reads!)

To borrow from some brand growth terminology from Romaniuk and Sharp….Hellmann’s is : Easy to Find, Easy to Think-Of, and Easy to Buy!

It’s more than that, for me, though. Hellmann’s is also Easy to Satisfy and Easy to Justify.

Easy to Satisfy being about Hellmann's voluptuous, creamy and tangy taste, its “almost-natural” ingredient list and even its war on waste. These are perceived differentiated (or non-differentiated) functional and emotional attributes that matter to me.

Easy to Justify being about its price and value. It’s not that hard to make me pay a bit more for Hellmann's versus an alternative that might be sludge-like or too vinegary. Hellmann's is actually also cheaper than many new emerging brands in the category, but its consistency and its mix-with-anything taste is hard to beat.

As you can now tell. I am a fan.

Graphic #2: The Mayo Category Entry Point and Purchase Pathway

Did Sir Kensington’s entice me to cheat a bit?

Yes. Until it seemingly disappeared, and then somehow lost its “differentiated” appeal for me and so I went back to my ole’ faithful. Mostly, that is. I still flirt a little bit with some newbies that appear now and again. You never know what delectable find might win my palate next. No such thing as absolute loyalty!

It's just mayo, Is it not? 👀

Why must I even overthink mayonnaise anymore?

There are over 35,000+ items in a supermarket store. I likely only buy about 150 brands more than once during the year. Some of those brands are heavy purchases, most others are not.

For tried-and-tested “staple” purchases I probably spend 10 seconds or less at the shelf. I would rather spend more time exploring the physical or digital aisles for new treats, new discoveries…Can I say new essentials or indulgences that are different? Even meaningfully different? (Thanks Kantar.) It certainly matters when I am in discovery-mode and give it some attention.

I also buy into Byron Sharps' "meaningless distinctiveness" insight [1] on how many buyers shop. I do not need data to prove that. My own shopping behaviors for certain categories and products/brands serve as a great anecdote.

Maybe, as I look to mindlessly replenish old favorites and mindfully explore new options… therein might lie some of the distinctiveness vs. differentiation insight nuggets.

Differentiation and heavy buyers

For emerging CPG brands, that have not yet achieved widespread physical and mental availability, it is my view and experience that it is the initial perceived or actual differentiation (easy to satisfy, easy to justify) that is foundational and necessary to first seed and establish the brand. Certainly for consumers that become heavy buyers and "fans".

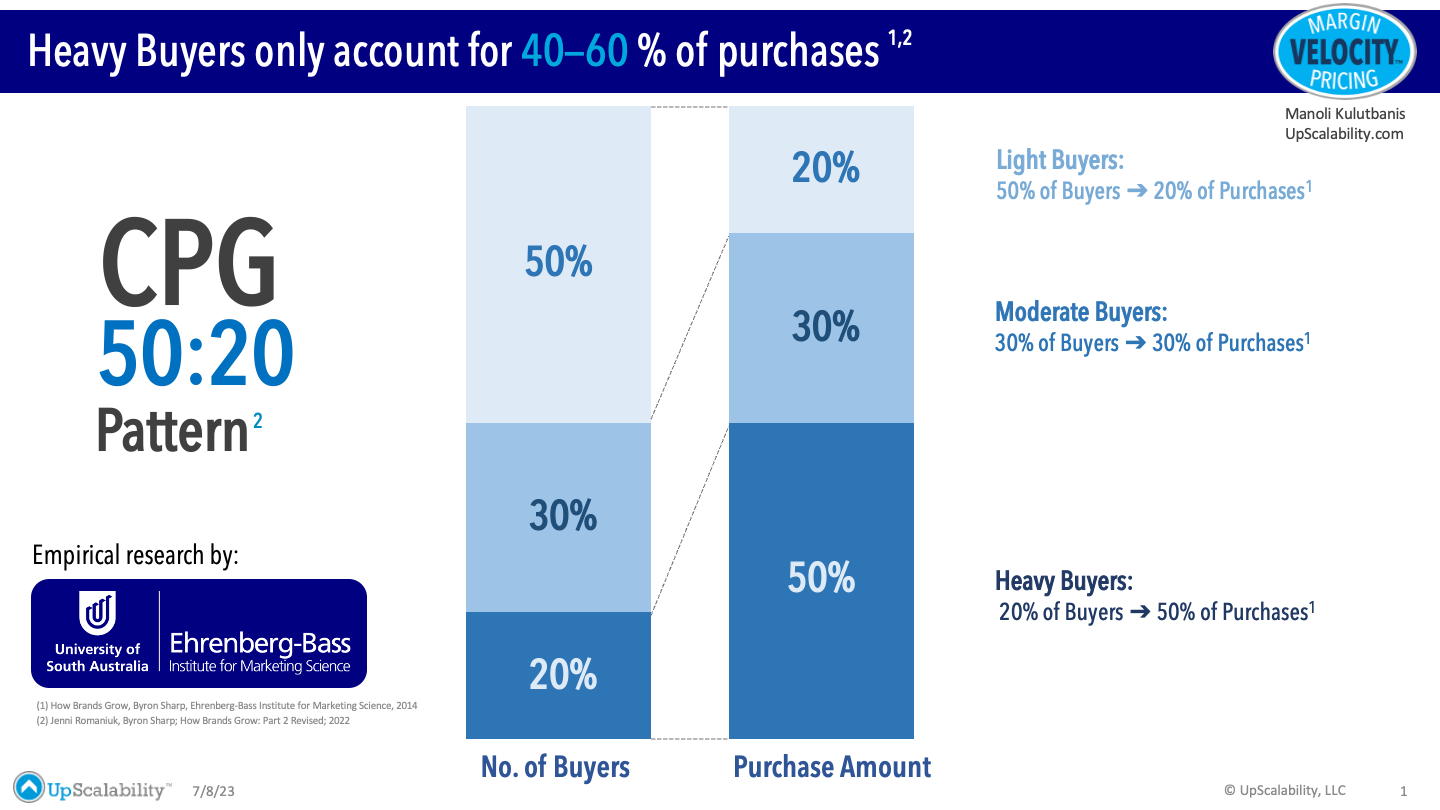

How else do you get to that initial and critical ~20% heavy buyer base that “only” accounts for ~50-60% of sales as Ehrenberg-Bass Institute research [1,2] has uncovered and that has been similarly validated by Jan-Benedict Steenkamp [3]?

(Jan-Benedict Steenkamp is the C. Knox Massey Distinguished Professor of Marketing at the University of North Carolina’s Kenan-Flagler Business School and the Executive Chairman of AiMark, a CPG marketing think tank)

Surely differentiation, perceived or actual, must also be necessary to replenish a a portion of that heavy buyer base?

Graphic #3: Buyer Cohorts and their Purchase Mix

I get it...for moderate and light buyers, mayo might not seem functionally differentiated. That is not to say that moderate or light buyers are not relevant in those early stages of an emerging brand in that category.

Just being available in the category and, perhaps on promotion could prompt that light buyer to purchase it just once or even twice that year or even over two years. Differentiating attributes might not be that important for that purchase other than its category function and price.

An emerging brand's early "differentiation is important" phase does also not imply that distinctiveness does not play a role. Standing out from a messaging and visibility perspective on the shelf (digital or physical) is critical, especially for brands that do not have the funds to invest in "longer-term" consumer and brand marketing.

Growth Curves: Penetration > Loyalty

Research led by Romaniuk, Sharp and validated by Steenkamp has also shown that, to scale and grow, you need penetration and reach. Even more so than loyalty.

Those ~80% moderate and light buyers matter for longer-term sales and profitability growth. 40-50% of Purchases!

And perhaps, as highlighted earlier, for moderate and light buyer cohorts, actual or perceived differentiation might not matter that much. Or maybe there was a time when that differentiation mattered but it has now faded away or even buried deep somewhere in their minds. But maybe, that has helped to nudge them as they enter a category to purchase a brand.

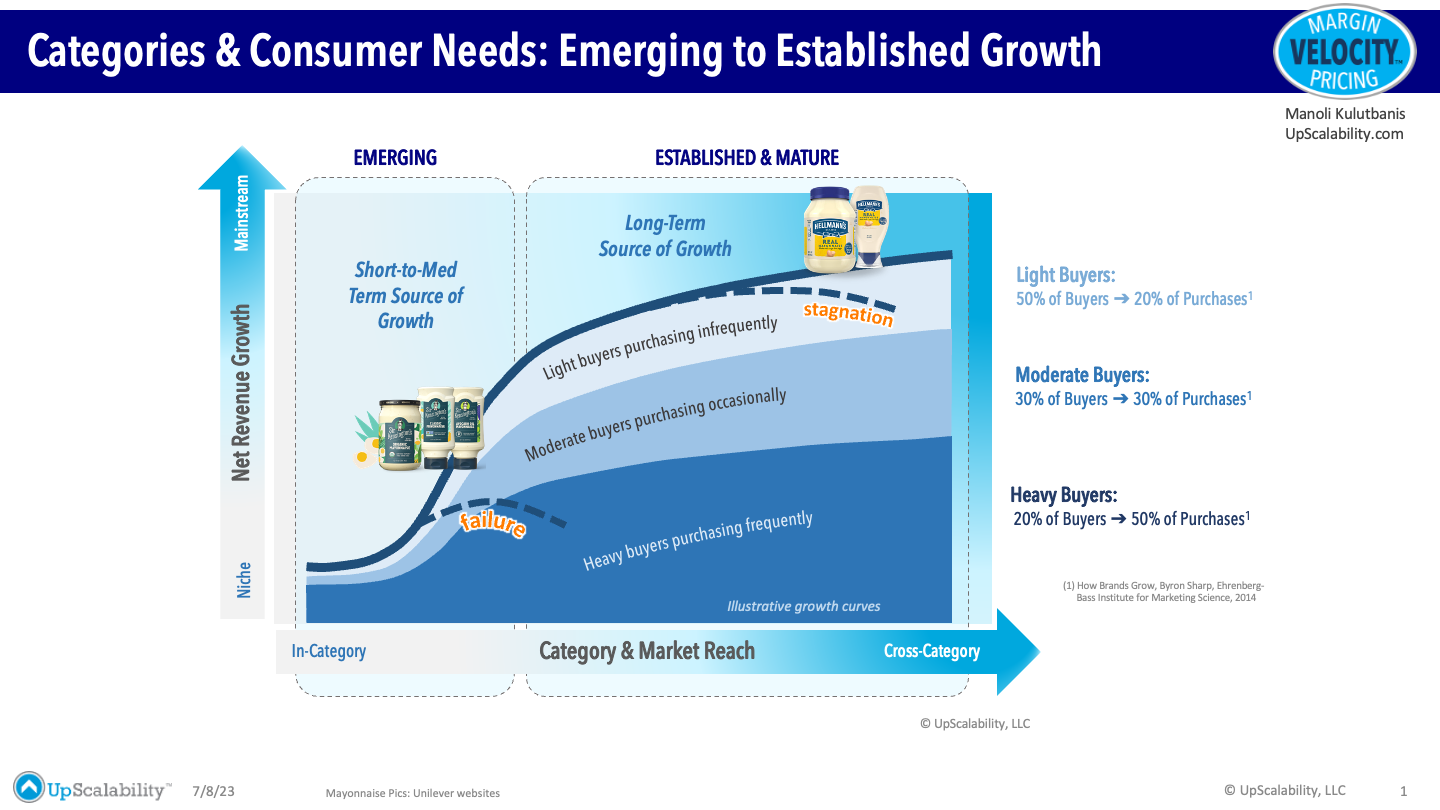

It’s difficult to talk about differentiation or distinctiveness, if you don't first contextualize how a successful emerging brand grows over time to become a mature and established brand.

Graphic #4: Buyer-Mix & Market Reach Growth Curve

For some brands that growth profile can be depicted by some a type of S-curve, Slow growth at first, then rapid expansion penetration and then an eventual slow down. Failure or stagnation can occur, as it does, for a number of market and brand-related reasons.

Moving vertically is about $ Sales, Velocity (rate of sales per unit distribution) and Pricing. Moving horizontally, to the right, is about Distribution Expansion and Household Penetration (within existing geographies and across new geographies).

No doubt, vertical and horizontal brand growth occurs can only occur when both mental and physical availability grow.

Hellmann's was painstakingly built over decades. A $2 Billion Dollar brand with a double-digit growth these past few years that is available in 65 countries. [4]

Christina Bauer-Plank (Global Brand Vice President Hellmann’s at Unilever) and her team certainly deserves a bubbly beverage of choice to complement their brunch and picnic sandwiches this summer.

Graphic #5: Hellmann's in a Conventional Supermarket

I am pleased that my purchases are helping a little bit! I am a Unilever alum and enthusiastically but defensibly biased.)

You can't talk mayo if you don't mention ketchup

I was saddened when Sir Kensington's Ketchup was discontinued in 2023. (It's how I was introduced to the brand!)

The Sir Kensington's brand was acquired by Unilever in 2017 from category-disruptor Scott Norton (ex Sir Kensington's CEO/CMO) and his co-founders.

Graphic #6: Sir Kensington's takes on Heinz

Sir Kensington's Ketchup was an awesome emerging brand and product that stood out with its clean ingredient credentials. I became an immediate fan. Premium priced it was, and from my own perspective the brand and product was Easy to Satisfy and Easy to Justify. I was rooting for the brand as a consumer and as a CPG professional and entrepreneur in the industry.

But to scale Easy to Satisfy and Easy to Justify is not enough. A brand (and variant) also needs Easy to Mind and Easy to Find. And, to do that it needs to be financially viable...and therefore Easy to Fund!

Too much competition in the ketchup category? At launch, there was nothing like Sir Kensington's ketchup in the category. A phenomenal tasting and textured ketchup. Differentiated from an ingredient and better-for-you list perspective at the time.

Insufficient Dollars and resources to support its growth? It did not "fail" because it was differentiated. It likely just could not get the scaled traction and market penetration that it needed at a price point that was viable for Unilever. Low gross margins and just not enough light and medium buyers to make it grow profitably. This is the viability trap for many emerging CPG brands.

The lesson is simple. A brand can scale and grow when it can finally escape its differentiation zone.

One thing is for sure. Building a sustainable CPG brand is actually not that easy.

Do emerging brands have more loyal buyers?

If I am interpreting it correctly, evidence, as per Ehrenberg-Bass, shows that the buyer mix of heavy, medium and light buyers generally remains in similar proportions during emerging and mature growth phases.

However they also found a replicable pattern, across categories and geographies that does show some nuances for small vs large brands. A marketing law.

The Law of Double Jeopardy [1,2]:

“Smaller share brands have fewer sales because they have many fewer customers (the first jeopardy) who are slightly less loyal (the second jeopardy).”

I struggled with this initially, because the prevailing view is that most of your growth as an emerging brand is sourced from heavy buyers and fans. There are many emerging brand founders that will attest to that.

Are there, perhaps, two buyer-mix possibilities during that emerging brand phase?

It is noted that a small brand does not have to be an emerging brand. A small brand can be an established brand that just happens to be small.

Could the dynamics be different for emerging brands? I will let the researchers answer that, but I will offer an initial hypotheses.

Graphic #7: Buyer Mix Levels at the Emerging Stage

My own purchase behavior, when it comes to mayo certainly, helped me understand how, even for Sir Kensington's, the Double Jeopardy Law was prevalent.

Sir Kensington's and Double Jeopardy

I had been leisurely (as my kids say) exploring ways to incorporate more natural food products into my daily and weekend food routines. Having discovered Sir Kensington's ketchup at Whole Foods during a demo and launch special (Demos work!!!), it was not that hard to give Sir Kensington's mayonnaise a try.

Firstly, the taste and texture was superb. Secondly, the differentiated (at the time) clean label ingredient list was well communicated and visible via the non-GMO and USDA Organic logos that acted as a proxy. If I recall correctly, a number of wellness-related blogs that I follow had had also raved and featured Sir Kensington's.

Sir Kensington's, the character, was (and remains) distinctive and added gravitas and character to what would otherwise have been a "faceless" brand.

You could say that, for about two years or so, I was a heavy buyer. (Apologies, Hellmann's)

Other buyers and consumers who also purchased Sir Kensington's, tried it but probably never became heavy or even medium buyers. The mayo did the job (or not); they maybe thought it was too expensive and they went back to whatever brand or repertoire of brands that they would normally purchase.

Emerging brands, usually when on special/promotion get that early promo-bump. But many of those buyers never become heavy buyers. Consumers are quite happy, every now and again, to try something once.

I can see how the buyer-purchase patter mix for Sir Kensington's can follow the Double Jeopardy Law. Sir Kensington's had less (way less) buyers and consumers than Hellmann's and purchased Sir Kensington's less frequently, given other options that were more available when needed.

DTC: Heavy Buyer Over-Concentration

Are are cases where, for emerging CPG brands, the heavy buyer mix is potentially higher than the mix when (and if) the brands reach a mature and established growth phase?

I believe there are.

Anecdotally you hear about a heavy buyer base from founders of digitally native or predominately DTC emerging CPG and emerging consumer goods brands.

That makes sense, if you consider that for most emerging CPG brands that have primarily depended on ecommerce channels...their offerings and messaging were highly targeted to segments of consumers who were seeking solutions that provided highly targeted (and differentiated) functional and emotional benefits.

And many of these predominantly ecommerce emerging brands deployed massive amounts on short-term performance marketing Dollars against highly targeted consumers to buy their "loyalty". Their heavy buyer mix, at least initially, was thus likely higher.

And, their funding and "eventual" viability was based on exactly that. "Optimizing" for heavy buyers. High CACs make the LTV of light buyers unprofitable. Almost forever.

This "over-indexed" heavy buyer mix for digitally native and DTC brands might also be their Achilles heel.

Many emerging digitally-native DTC brands have hit a wall. I suspect that a major factor for the wall is that they have eventually run out of sufficient "heavy buyers" to keep their flywheel moving.

There, also, are just not enough moderate and light buyers that naturally (and profitably) churn regularly!

I suspect that the highly targeted consumer and highly loyal fan base kept those DTC brands going, albeit unprofitably due to the unsustainable high levels of paid CAC and last mile delivery costs. (Don't worry. Amazon, Shopify, 3PLs, ROI "optimizers" will be ok. They provide the picks and shovels.)

It is why many DTC brands are jumping into bricks 'n mortar channels. Not that this will necessarily save them. Especially within the US, where the overall trade marketing plus consumer marketing spend needed to compete in bricks 'n mortar channels could be nearly double that in Europe and Asia.

(Some time ago, I wrote an article on e-commerce vs bricks 'n mortar economics that might help explain why DTC can be challenging from a profitability perspective. Here is the Link.)

Heavy Buyers: Emerging Premium CPG Brands

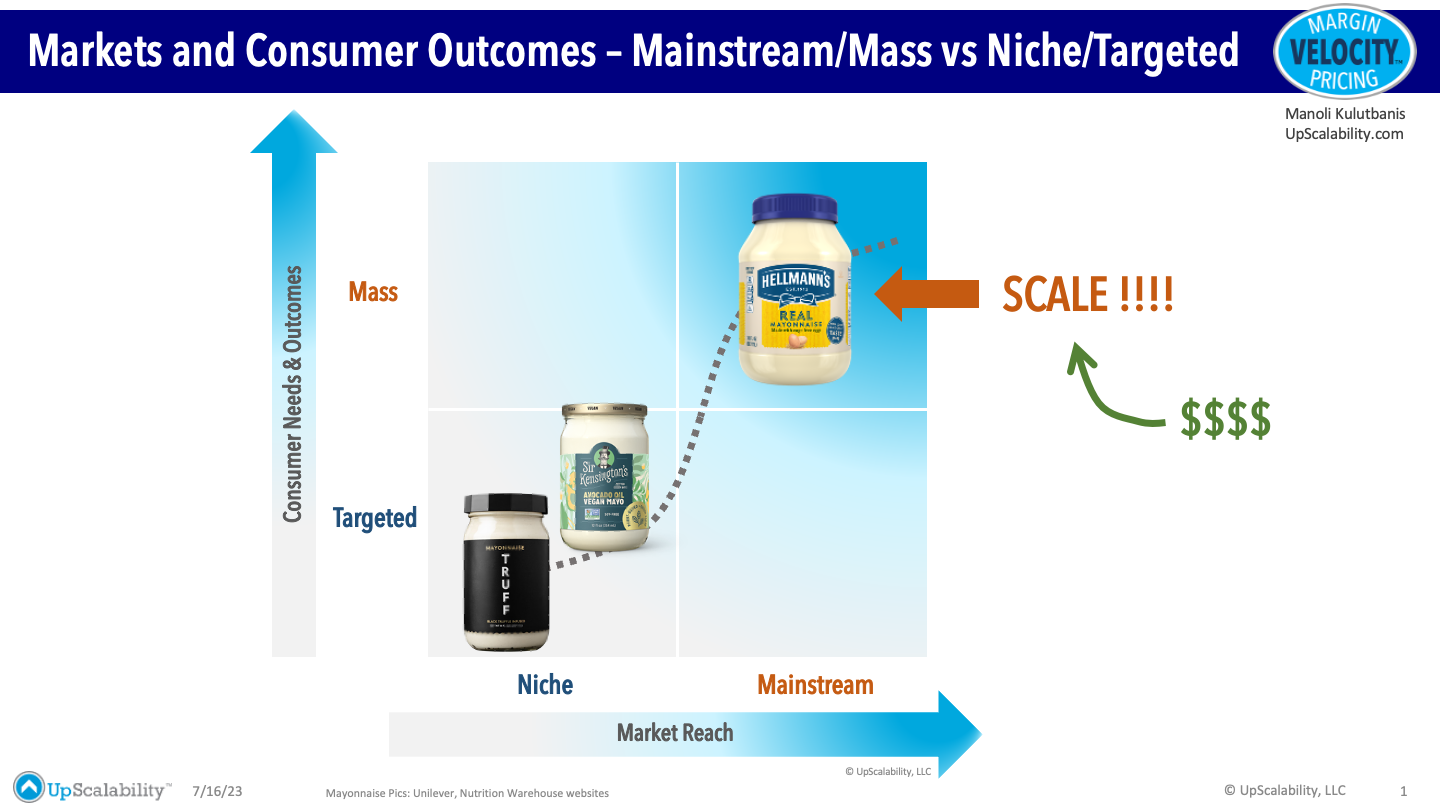

This over-indexing of heavy buyers (relative to Ehrenberg-Bass findings) could also be true for emerging CPG brands that are sold predominantly via bricks 'n mortar channels.

But it seems that these brands, tend to be premium and above-premium brands that are targeting emerging and growing niche sub-categories (e.g. Keto, Gut Health, FODMAP, Gluten-free, Immunity, Fitness Recovery etc.).

These brands have product attributes that are usually highly or relatively "differentiated" versus mainstream or established brands that target broader outcomes to a wider consumer audience. These potential and actual buyers are also highly targeted with digital and on-the-shelf messaging.

Therein lies the problem though. Niche sub-categories, highly targeted and with relatively small buyer cohorts who are devoted and big fans. Often, there just are not enough of them, beyond "Whole Foods and Sprouts" that can sustain those brands over the long term.

If the premium brand's functional and emotional outcomes are meaningless to moderate and light buyers and if that brand cannot recruit those buyers then that brand (often leveraged with investor capital) will struggle to scale. And, likely fail.

Dr. James Richardson (Cultural Anthropologist & CPG Strategy Consultant) has analyzed and writes extensively on how only a small number of premium emerging brands have grown exponentially [5,6,7].

Given limited marketing funds, Richardson contends that, at the emerging stages, brand outcomes should be messaged according to their "functional" attributes and benefits that are " close to the experience of using the product".

Richardson's insights into premium "skate ramp" emerging brands does not just dwell on the importance of functional attributes and lots of fan-based cohorts initially. Often highlighted in his analyses of emerging premium brands that did grow exponentially, was that these brands were able to "find a mass-market outcome and create a modern way to achieve it"

Back to ketchup for a moment. In Feb 2023, Scott Norton penned a "eulogy" post on Medium for Sir Kensington's Ketchup. This paragraph stood out for me:

"We’d also like to look back and take a moment to recognize what Sir Kensington’s ketchup stood for and the impact that it ultimately had on changing the market, as a case study in the food industry. At the time it launched, taking high fructose corn syrup out of ketchup was considered innovative — now it’s expected for any new food product launching today. Since then, every last aisle of the supermarket has been upgraded, diversified, and so many creative companies have come out of the woodwork." [8]

Norton and his team certainly shook up the center-aisle. The industry needs more Nortons. The lesson here is that functional differentiation offers only a temporary competitive advantage reprieve if it can eventually be replicated and become the "norm".

Once again, to grow you need a brand that can escape its "initial" differentiation edge if it wants to grow and scale.

Graphic #8: Illustrative Mayo Consumer Outcomes vs Market Reach Matrix

Premium and niche brands fail when when there are:

Insufficient heavy buyers or fans to scale households and geographies, and

Insufficient cohorts of occasional medium and light buyers that "stand on the shoulders" of those heavy buyers.

Another reason many emerging premium brands fail is that their initial low margins never really decrease with scale, given that pricing (per pack) actually can competitively decrease as mass outcomes and mainstream markets are pursued.

Sure, their COGs might decrease as scale advantages are gained, but their suggested retail price (and net price after promo) will likely decrease! Fast-growing, Liquid Death and Olipop are going to be finding that out soon as they continue their penetration gains.

It’s not that niche brands with highly targeted outcomes cannot be profitable. It’s just that it is just more difficult for them if they want to become really big brands.

CPG is a scale game.

Any Celebrity Packaged Mayonnaise Yet?

Marketers watch enviously as media celebrities, often many years younger, launch and capture unprecedented mental and market availability reach in super concentrated periods of time.

Within food and beverage, Feastables from Jimmy Donaldson (aka, MrBeast) and Prime Hydration from Logan Paul and KSI comes to mind.

That upslope of that S-growth curve is steep. Very steep. They have achieved growth that takes decades to build for most brands that do not have that powerful and viral media reach.

Fame, in its literal sense, coupled with exponential digital dispersion has changed how quickly mental and therefore physical availability can be “spread.” But the faster you rise, the faster you reach that peak.

Virtual brand, MrBeast Burger was launched in late 2020, as a deliver-only brand and serviced by partner restaurants or "ghost kitchens". A bricks 'n mortar location was opened in Sep 2022 where "some 2,000 people stayed overnight in the mall to be first in line for the restaurant opening" according to MrBeast and as reported by Lisa Fickenscher of NYPost [9].

In June 2023, Shay Robson of Dexerto reported that "YouTube star MrBeast has revealed he’s “moving on” from his Beast Burger restaurants in order to shift his focus to Feastables." [10]

Up until then MrBeast was available via 2,000 locations. Red Robin, which operates over 500 burger outlets and a key partner of MrBeast Burger confirmed to Restaurant Dive that "will stop offering virtual brands, including MrBeast Burger". [11]

(I wonder what mayo MrBeast Burgers used, if any?)

Nothing wrong with innovating, testing, launching, learning....and even failing. That is how industries, markets, categories, technologies and economies prosper.

Often overlooked, however, by emerging CPG brand founders and influencers/celebrities is that successful brands need to be built to last 50 Years plus. Celebrities, like their fandom can come and go. It’s the brand that should be the celebrity. That’s the hard everyday slog that makes brands survive most fan fads.

Also not surprising is how celebrity packaged brands that are acquired by large CPG companies to bolster and mask their own stagnation in mainstream core brands, often struggle to maintain momentum and relevance for those brands.

Any upcoming research and insights here... Ehrenberg-Bass, Kantar?

Bothism...The quest for a rational approach

Within marketing circles and discussions, I have been fascinated with the increasingly rigorous discussions and debates about differentiation versus distinctiveness. These discussions have, for the most part, moved the industry and profession forward.

Attention sells, and in true marketing splendor, Mark Ritson (Brand Consultant, Columnist & Former Marketing Professor) has upped the ante and is provocatively leading the vocal charge for Differentiation AND Distinctiveness. (Ritson is a highly effective writer and communicator!)

Coining "Bothism", Ritson pushes back on what he sees as extreme marketing or research positions that pits Differentiation and Distinctiveness against each other.

Ritson [12] contends:

"For marketers, the key lesson is that when they build brands they need to divide their attention and their efforts across both concepts. On a single page of paper you need a list of the distinctive brand assets that will deliver distinctiveness. But beneath that list you also need a clear, tight brand position that – if correctly executed – will result in valuable, relevant, relative differentiation."

Bothism is not just Differentiation and Distinctiveness. Ritson, as he has acknowledged, was also inspired by Tom Roach's vigorous defense of the work of Les Binet and Peter Field who have published extensive findings on the mix of short term (performance marketing & trade marketing) versus long term (consumer marketing & brand marketing) spend.

Tom Roach (VP Brand Strategy of marketing performance company Jellyfish) had this to say [13]:

"Short-termism and long-termism are both just wrong-termism. So let’s end the false choice between long and short-term marketing tactics, maximise the compound effects of getting them working together in harmony, and start to close the value-destroying divide between ‘brand’ and ‘performance’ marketing. It’s limiting marketing effectiveness and brand growth, when we’ve never needed them more."

"Long-term growth always has its roots in the short term. The two are connected, influence each other, and if you get the two working perfectly in harmony together, you’ll achieve the strongest, most sustainable growth possible."

The short-term versus long-term brand building investment discussion is relevant to the growth curve too, especially for emerging CPG brands and now more than ever DTC CPG and consumer brands.

In hyper-competitive categories were shelf-space (physical or digital) is limited the amount of short-term spend is critical for emerging brands to get up that growth curve. But those costs have increased almost astronomically. Especially in light of deep-pocketed large-brand incumbents that can out-promote and out-last their nimbler challengers.

In the US, its not unheard of that emerging brands have to spend over 20 to 25% of their gross sales to their distributor or retailer (if direct) on price promotion and other trade marketing activities.

Its not that different for DTC. In fact it could easily be worse. (See my article on ecommerce margins, if you want to see why).

But as per Binet* and Field* (and as Roach amplifies) you also need to go Long. That is how you get to the mature and established growth zone, That is how you build the mental availability to support the physical availability that allows you to grow penetration and distribution.

You need both short and long.

*Les Binet is Group Head of Effectiveness at adamandeveDDB. Peter Field is Independent Marketing and Advertising Professional. They have published extensively on marketing effectiveness but are most well known for "The Long and Short of It, Balancing Short and Long-Term Marketing Strategies" [14]

Kantar, a global and leading data, insights and consulting company that works with many large CPG brands use their Meaningful Different Salient (MDS) framework to measure "the value of brand equity accumulated in the minds of consumers – its impact on penetration and market share; its impact on willingness to pay, and its impact on future growth potential." [15]

Kantar, adopting a more polite approach on the differentiation-distinctiveness discussion, are also proponents of bothism, although they see distinctiveness as an element that touches both differentiation and salience.

The following paragraph stood out for me in an article, co-authored by Mary Kyriakidi (Global Thought Leader at Kantar) with Graham Staplehurst (Director, Thought Leadership at Kantar BrandZ):

"Differentiation is the intended brand image that you, as a marketer, hope to achieve in the mind of the consumer through positioning. Brand differentiation offers an opportunity for brands to go beyond the borders of distinctiveness, to find product-based, experience-based, even emotionally based differences that break through consumers’ expectations of parity. It’s then that a product becomes “more than a product” as Bullmore and King confer – it “begins to satisfy needs over and above purely functional needs. And if it does that, then it’s worth more money”. [16]

It's not just mayonnaise that helps me contextualize bothism. I was fortunate to have spent some time in the beer industry. (A great sandwich with a great sessionable beer goes well on a lazy Saturday afternoon.)

Norman Adami (Former Miller Brewing Co and SAB CEO) who took the challenger fight head-on to behemoth Anheuser-Busch and turned around a stagnant Miller Lite brand at the time ...did not succumb to the either-or trap.

Rather, Adami (as was his modus operandi) acknowledged the complexity and reality of competitive markets and the ambiguity that they posed. For Adami it was about challenging the entire organization and its distributor partners to embrace the Both-And (as he called it) mentality and culture that was needed to win. And he did.

A chicken and egg mayo sandwich

Unfortunately, some discussions have also devolved into little food-fights. Is it the chicken or is it the egg? (Spoiler alert: they both go well with a generous helping of mayo...the chicken and egg , that is) (Vegan, if you must.)

Discourse is healthy. Nastiness and hubris are not. Science, research, and facts keep brands grounded. Evidence-based marketing science has changed the way we think about and how we plan for growth.

Big ideas, innovative formulations, dreams and creativity…an absolute must in brand messaging that can bring that to light. Nobody in this turf war disputes that.

Bothism (or Both-And) does not imply "sitting on the fence", "playing it safe" or "averaging your bets". Bothism is not necessarily about balance.

Bothism is about knowing and finding creative ways to overcome and manage TOUGH TRADE-OFFS that you make when applying constrained resources to deliver a market outcome. Short-term and long-term. That is what separates winners from losers.

The marketing world: As it is and as it could be

In the wake of clarifying thoughts and view points, I came across a fountain of wisdom that has been insightfully articulated, on a number of occasions, by Roger Martin (Strategist, Advisor and co-author of playing to Win written with P&G's legendary former-CEO AG Lafley.)

Drawing from Aristotle, Roger Martin and Tony Golsby-Smith (Chairperson, Mimesis Technology) share some insights that inadvertently can help us understand and better contextualize the differentiation vs. distinctiveness discussion. [17]

"Science explains the world as it is; a story imagines the world as it could be."

They highlight that there are two possibilities:

A marketing world where "Things that cannot be other than what they are"...driven by evidence that is derived via cause-and-effect analyses.

A marketing world where "Things can be other than they are" where than can be "a future that can be different from the past". This is the world of creativity, stories and innovation.

It is this second marketing world where I believe the realm of differentiation mostly sits. As Ehrenberg-Bass asserts, functional differentiation can be copied and as such any competitive advantage from that innovation-based differentiation can quickly dissipate.

I am more allured, however, by perceived differentiation and how that gets etched in consumers and buyers minds. Could it not be true that perceived differentiation is about "constructing persuasive narratives" that creates one of the elements for mental availability? Surely this is where creativity and story-telling sits.

And if you can do this better than your competitor, then you have differentiated.

As Martin and Goldby-Smith remind us: "The absence of data does not preclude possibility".

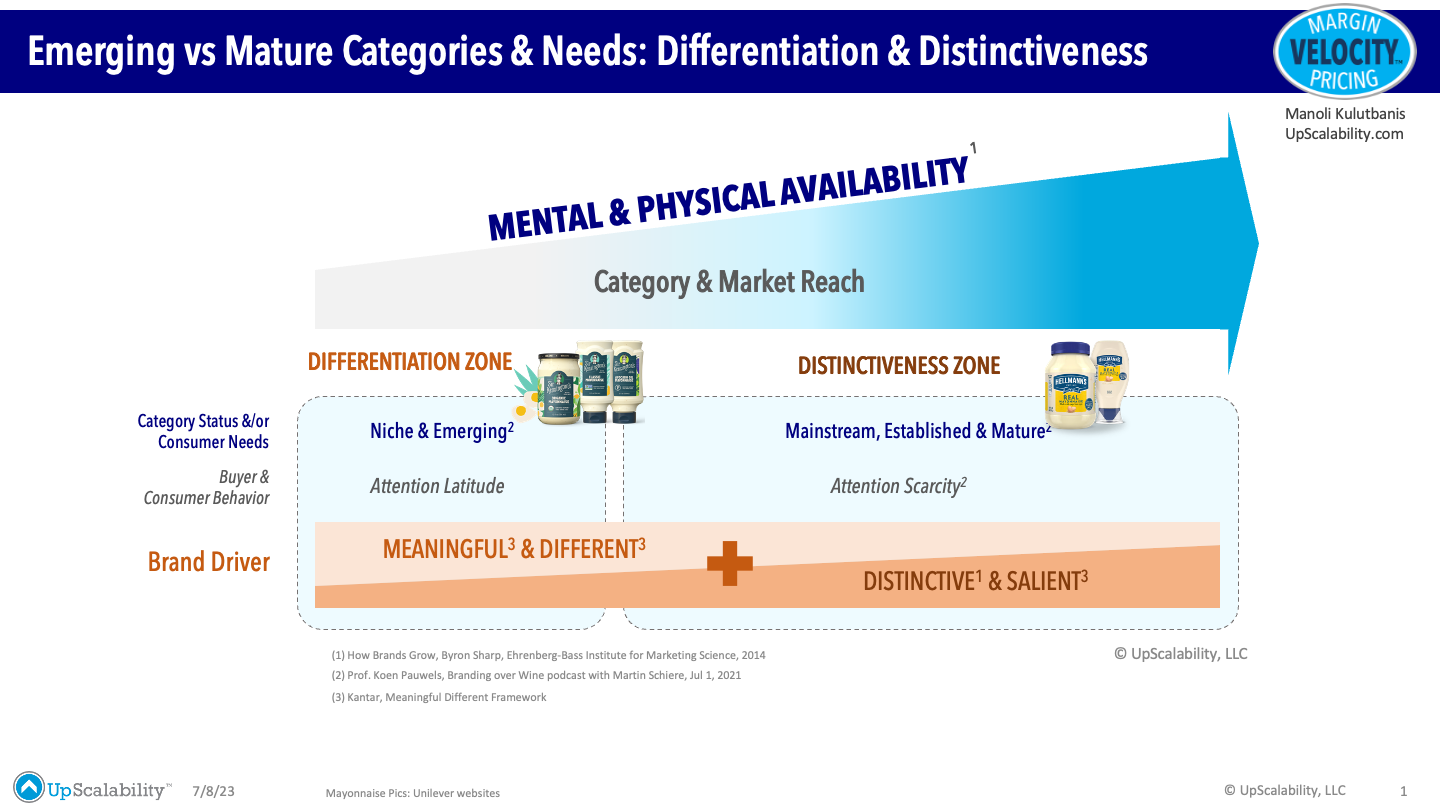

Emerging vs Mature Categories & Needs

A 2021 podcast interview featuring Prof. dr. Koen Pauwels (Distinguished Professor of Marketing at Northeastern University) with Martin Schiere (Cofounder & host at Brandingmag) got me thinking about how to pull everything together in my own mind.

Pauwels discussed his research that uncovered the extent to which differentiation mattered to a) small brands versus larger brands, and b) emerging versus mature markets.

"Differentiation matters most for smaller brands vs. larger brands and then in emerging countries vs. mature markets. If you are a smaller brand and want to challenge the status quo, then differentiation matters a lot” [18]

What really caught my ear, however, was the reasoning behind the extent of differentiation and its relationship with the "amount" of attention that consumers commit with small vs large brands and in emerging vs mature markets.

“Differentiation is harder to achieve in mature markets, likely because people don’t pay that much attention to your brand. We are mostly creatures of habit. We don’t have much time to spend on brands. Time is our scarce resource in life"

The research uncovered that “in emerging markets people do pay more attention to brands”. Attention was "not that scarce in emerging markets.”

The implication is similar, I assume, for emerging brands where heavy category consumers might be searching for better solutions and brands that might offer actual or perceived attributes that can do a better job than the brand they currently favor.

Schiere summarized it perfectly...

“Smaller brands need to differentiate, and larger brands need to focus on salience and/or distinctiveness”

What if differentiation and distinctiveness is also about the extent and depth of attention that a brand needs versus the attention that consumers and buyers are willing to give as they shop?

What if differentiation and distinctiveness can be thought about as broad zones where they might have a lesser or greater influence. Not that there are clear boundaries or clear beginnings and ending of those zones.

For me, differentiation and distinctiveness extend across the entire width of penetration reach, just in differing proportions. And this is how bothism can exist.

The Kantar model fits and so do the laws of Ehrenberg-Bass.

More Meaningful & Different at the emerging phases (but that are essential for the foundation of mental availability) and more Distinctiveness & Salience for mature and established brands (where mental availability requires the instant trigger).

Attention Latitude thats important for niche and emerging brands and Attention Scarcity that is a reality for mainstream, established and mainstream brands.

Graphic #9: Differentiation-Distinctiveness Sliding Scale

Of course when buyers shop, they find are faced with emerging and mature brands that co-exist on the same shelf. And this is where packaging design, purchase incentives, point-of-sale collateral, past advertising all need to come in play. Distinctiveness might have an edge here.

Assembling the club sandwich

Combining the Buyer Mix & Market Reach Growth Curve and the Differentiation-Distinctiveness Sliding Scale, in one graphic, might help with visualizing and further discussing the scope and impact of differentiation and distinctiveness.

For me, puzzles need to fit so that at least I can make some sense of the world around me.

Graphic #10: Differentiation & distinctiveness at all the stages of growth

While the graphic depicts a Differentiation and a Distinctiveness Zone, it must be emphasized that these zones are illustrative and are highlighted to show that:

Some form of differentiation, actual or perceived, is usually needed as a messaging and purchasing trigger for emerging brands (or new innovations) to capture attention and be chosen versus an alternative. Especially when buyers are, perhaps spending a little bit more time (e.g. searching or "label-reading" for better solutions.)

Some form of distinctiveness, whether it is a sensory cue that makes that brand stand out in that category for a first-time buyer or whether it is built over many years to trigger a mental nudge that is needed in mature categories and for mature brands. Distinctiveness, as per Ehrenberg-Bass, helps with those instantaneous decisions for categories and products where buyers don't want to spend too much time thinking and deciding about what to buy.

Differentiation is not exclusive for emerging brands and categories and distinctiveness is not exclusive for mature categories.

Differentiation (actual or perceived) is also a factor in the mature phases of a brand and in mature categories. For example, in mature categories and among powerful mature brands, an emerging brand will have to work harder to creatively elevate its differentiating credentials (if that is deemed important) so that it can have a chance of a purchase.

Distinctiveness is also not just found in the mature or later stages. For many emerging brands it might be critical in those emerging phases to stand-out.

I emphasize a sliding scale. More Meaningful and Difference (as per Kantar) on the left hand side for new brands but that is then "embedded" over time as part of the mental availability needed in mature phases. And, more Distinctiveness and Salience where attention scarcity is a factor in the busy every-day life of a buyer.

In the discussion on long versus short term marketing investment, Tom Roach summarized it well when he said... "The Long through the Short of It".

I like that. Maybe you could then also say that while distinctiveness can work without differentiation, great emerging brands grow via Distinctiveness (in the long run) through Differentiation (in the short run).

Differentiation does not matter much, if it's not scalable

Differentiation, actual or perceived, is often discussed within the context of uniqueness, meaningfulness, and/or relativity. All this is relevant.

Differentiation, actual or perceived, is NOT SUFFICIENTLY discussed within the context of scalability and/or fundability (the capacity to invest marketing Dollars in growth).

The proliferation of emerging CPG brands over the last decade and a half was clearly evident on the physical and digital shelves. Retailers and distributors were hungry to capture incremental margins given stagnant mainstream category growth.

Even in mayonnaise and condiments, a once-sleepy category with well-known well-trusted stalwarts, brand and SKU proliferation has accelerated. For example, Pack sizes, Jars/Squeezable Bottles, Dairy/Non-Dairy, Organic/Regular, Vegetable/Olive Oils, Plain/Flavored. Not to mention blurring with other condiment sub-categories like sauces and relishes. Thanks Mayochup.

Proliferation also goes hand-in-hand with:

Hyper consumer segmentation and targeting.

Acceleration of category blurring.

Under the innovation cape, these brands and variants keep on appearing. All are touting uniqueness and differentiating attributes. Actual and perceived.

Most will be emulated quickly as Ehrenberg-Bass reminds us.

Some innovations are incrementally necessary to maintain the relevance of the brand. Some innovations and new brands are so niche that they will likely never find sufficient heavy and medium/light buyers to be viable in their own right.

And some entrants are absolutely differentiated, tasty, deliver the relative differentiated attributes that could appeal to large audiences...but the brands and companies just do NOT have sufficient marketing funding and viability runways to build the brands sustainably.

Nowadays, brands with core variants that can cater to mass consumer outcomes in mass markets win! It is as simple and as challenging as that. Hellmann's has showed us how (and why)!

And for those that do scale its ok if those attributes are not that differentiated anymore.

Not that you can't make money in niche markets with niche buyers. Your growth will just be limited. Scaling and funding aspirations need to be muted and right-sized.

Large-scale growth, which most brands aspire to, is depended on large buyer cohorts, long time runways and most importantly lots of investment Dollars for ongoing consumer marketing and for the expansion of physical distribution and market penetration. In other words...Mental and Physical Availability.

This is not to say that Differentiation is therefore irrelevant. For some brands it matters for capturing those heavy buyers. It matters for keeping the core brand refreshed even if those differentiated. It matters for gathering ongoing pockets of many incremental buyers and opportunities...if you can support that.

CPG is a Scale Game

The explosion of brand/SKU proliferation was powered by the ease of market entry of 1000s of emerging brands driven by cheap funding, lower barriers of entry for ecommerce channels, accessible contract manufacturing capability and the stagnation of mainstream brands.

We have forgotten that for most CPG/FMCG brands it is the "slow slog" and ongoing acquisition of light buyers and increased household penetration that builds the last layers of the profit pie.

CPG is a scale game. Household penetration and distribution! On the back of strong velocities and rational pricing discipline! And strong brand investment funding!

One thing that is important to call-out, even shout it out LOUD:

Maximizing brand sales growth is not the same as maximizing brand margin growth!

This is the one area were bothism does not apply.

Please share this article if it was useful. I publish CPG margin growth, pricing and velocity perspectives and insights on a “regular-irregular” basis. You can sign-up here for those articles to be delivered directly to your inbox.

I also post thoughts and musings on LinkedIn. You can follow me here. Comments and criticisms for this article are welcome.

Manoli Kulutbanis

BTW: Don’t forget the Hellmann’s!

References

[1] Byron Sharp, How Brands Grow, Ehrenberg-Bass Institute of Marketing, Oxford University Press, 2022

[2] Jenni Romaniuk & Byron Sharp, How Brands Grow: Part 2 Revised, Ehrenberg-Bass Institute of Marketing, Oxford University Press, 2022

[3] Jan-Benedict Steenkamp, Do heavy buyers really account for 80% of your sales volume?, LinkedIn article, Aug 29, 2017

[4] Unilever, Behind the brand: What's Hellmann's secret sauce for success?, Unilever.com News, Nov 25, 2022

[5] James Richardson, Ramping Your Brand: How to Ride the Killer CPG Growth Curve; PGS Press; 2019

[6] James Richardson, Emotions are Not a Strategic Outcome, Premium Growth Solutions (PGS) Article, Jul 14, 2023

[7] James Richardson, The Forgotten Outcome in CPG, Premium Growth Solutions (PGS) Newsletter, Dec 1, 2023

[8] Scott Norton, Sir Kensington’s Ketchup: A Eulogy, Medium, Feb 21, 2023

[9] Lisa Fickenscher, MrBeast draws thousands to YouTube star’s new burger joint at American Dream mall, New York Post - Business, Sep 5, 2022

[10] Shay Robson, MrBeast “moving on” from Beast Burger restaurants after just two years, Dexerto,com - Entertainment, Jun 18, 2023

[11] Aneurin Canham-Clyne, Red Robin pulls the plug on MrBeast Burger and its own virtual brands, Restaurant Dive - Dive Brief, Jul 14, 2023

[12] Mark Ritson, In the battle between salience and differentiation, Bothism wins, Marketing Week, Oct 5, 2022

[13] Tom Roach, The Wrong and the Short of it, TomRoach.com, Nov 15, 2020

[14] Les Binet & Peter Field, The Long and Short of It, Balancing Short and Long-Term Marketing Strategies, Institute of Practitioners in Advertising (IPA), 2013

[15] Kantar.com, About page

[16] Mary Kyriakidi & Graham Staplehurst, Modern Marketing Dilemmas: Is Brand Differentiation An Effective Way To Reduce Customer Price Sensitivity?, theBrandberries, May 17, 2022

[17] Roger L. Martin, Tony Golsby-Smith; Management is much more than a science, Harvard Business Review, Sep-Oct 2017

[18] Koen Pauwels, Branding over Wine podcast with Martin Schiere, Jul 1, 2021